Opportunity Knocks #37 - MLK and the Purpose of Education

Every Monday, I share reflections, ideas, questions, and content suggestions focused on championing, building, and accelerating opportunity for children.

In 1947, a young Martin Luther King Jr., then just an 18-year-old student at Morehouse College, penned an essay for the campus newspaper focused on the purpose of education. In it, King underscored what he believed was the dual purpose of education: to create “utility”—e.g., to help learners build critical thinking and practical skills that enhanced their ability to thrive—and to advance “culture”—e.g., to help learners dismantle personal ignorance, overcome prejudices, and build moral fiber.

“It seems to me that education has a two-fold function to perform in the life of man and in society: the one is utility and the other is culture. Education must enable a man to become more efficient, to achieve with increasing facility the legitimate goals of his life. . .But education which stops with efficiency may prove the greatest menace to society. The most dangerous criminal may be the man gifted with reason, but with no morals.”

He argued that the best way to do this was via an education system that empowered individuals to think for themselves and engage in discourse about complex and controversial issues.

“Education must enable one to sift and weigh evidence, to discern the true from the false, the real from the unreal, and the facts from the fiction.”

King's words also eerily described challenges in contemporary education (he would likely be disheartened).

“Even the press, the classroom, the platform, and the pulpit in many instances do not give us objective and unbiased truths. To save man from the morass of propaganda, in my opinion, is one of the chief aims of education.”

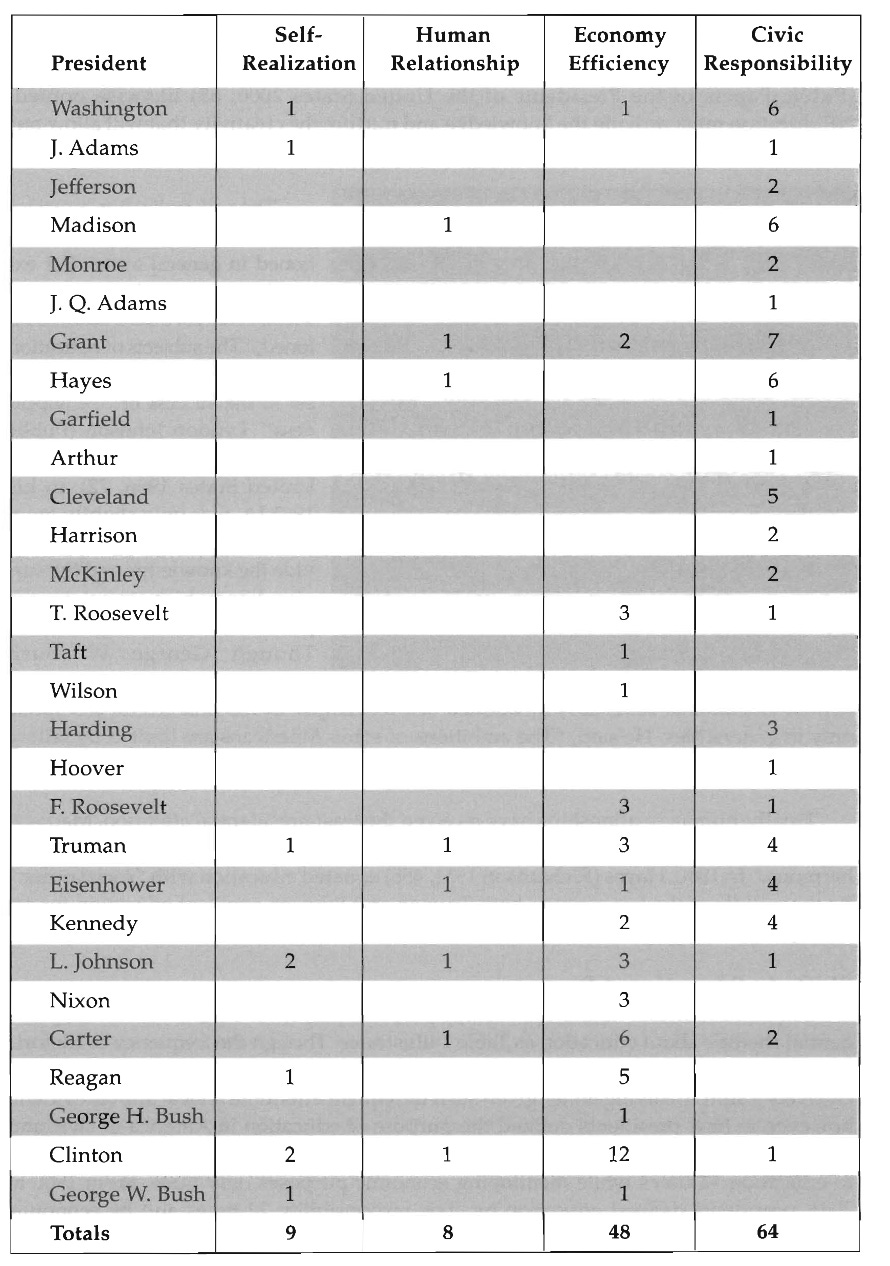

King was joining a long history of philosophers and educational theorists who considered the purpose of education. In the United States, two aims have gained the most attention: civic responsibility and economic efficiency. Below is an analysis of the frequencies of the purpose of education articulated by presidents in the State of the Union and inaugural addresses between 1790-2002. The data points to a shift towards economic efficiency.

Higher education is now facing systemic challenges including, runaway prices, shifting generational learning preferences, student debt, alternative post-secondary pathways, unclear paths to labor-market success, and dissatisfied faculty. Underlying these obstacles may be a more fundamental challenge, that higher education has gotten away from its dual purposes of efficiency and moral and cultural awareness as King proposed (recent events on college campuses underscore the latter).

Maybe the way to renew confidence in higher education is to return to King Jr.'s vision of a system that equips individuals with the skills they need to thrive and to navigate moral complexity, e.g., the tools to critically analyze information—without dismissing it if one disagrees—discerning truth—without cherry picking the truths that best align with one’s ideologies, social constructs, and cultural sensibilities—and engaging in constructive dialogue—without vilifying those with different perspectives.

Well, all that and dramatically cutting costs without impacting the quality of education (e.g., by reforming student aid, incentivizing competition based on the value of labor market outcomes including by leveraging debt-to-earnings tests, moving federal accreditation policy further towards an outcomes-based framework, reducing middle management with no clear impacts on student learning or wellbeing, and improving net price transparency).

Until next week be calm and be kind,

Andrew

The Purpose of Education

Martin Luther King Jr., 1947

As I engage in the so-called “bull sessions” around and about the school, I too often find that most college men have a misconception of the purpose of education. Most of the “brethren” think that education should equip them with the proper instruments of exploitation so that they can forever trample over the masses. Still others think that education should furnish them with noble ends rather than means to an end.

It seems to me that education has a two-fold function to perform in the life of man and in society: the one is utility and the other is culture. Education must enable a man to become more efficient, to achieve with increasing facility the ligitimate goals of his life.

Education must also train one for quick, resolute and effective thinking. To think incisively and to think for one’s self is very difficult. We are prone to let our mental life become invaded by legions of half truths, prejudices, and propaganda. At this point, I often wonder whether or not education is fulfilling its purpose. A great majority of the so-called educated people do not think logically and scientifically. Even the press, the classroom, the platform, and the pulpit in many instances do not give us objective and unbiased truths. To save man from the morass of propaganda, in my opinion, is one of the chief aims of education. Education must enable one to sift and weigh evidence, to discern the true from the false, the real from the unreal, and the facts from the fiction.

The function of education, therefore, is to teach one to think intensively and to think critically. But education which stops with efficiency may prove the greatest menace to society. The most dangerous criminal may be the man gifted with reason, but with no morals.

The late Eugene Talmadge, in my opinion, possessed one of the better minds of Georgia, or even America. Moreover, he wore the Phi Beta Kappa key. By all measuring rods, Mr. Talmadge could think critically and intensively; yet he contends that I am an inferior being. Are those the types of men we call educated?

We must remember that intelligence is not enough. Intelligence plus character—that is the goal of true education. The complete education gives one not only power of concentration, but worthy objectives upon which to concentrate. The broad education will, therefore, transmit to one not only the accumulated knowledge of the race but also the accumulated experience of social living.

If we are not careful, our colleges will produce a group of close-minded, unscientific, illogical propagandists, consumed with immoral acts. Be careful, “brethren!” Be careful, teachers!